QUINTO MARTINI - PAINTING by Marco Fagioli

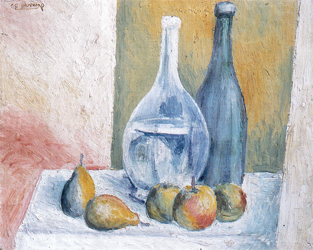

Still life with fruit and bottles, 1932 ca.

Still life with fruit and bottles, 1932 ca. Quinto Martini, Studio Edizioni Scelte, 1999

Landscape

LandscapeQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

Woman ironing

Woman ironingQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

Woman harvesting hay

Woman harvesting hayQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

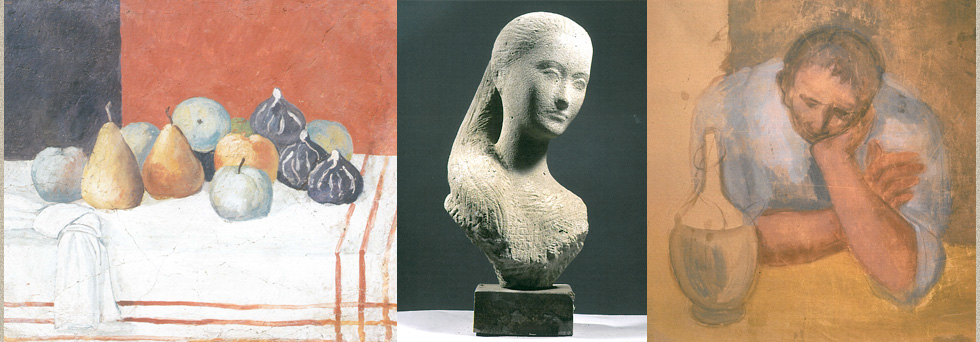

Great still life

Great still lifeQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

Woman washes her feet

Woman washes her feetQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

Rigour and consistency of Quinto Martini painter

In the clear light of his studio in Seano and in the more watery light of his studio in dei Della Robbia street in Florence, Quinto Martini has been weaving for decades, through painting, a kind of ongoing dialogue with himself, the men, and the culture of the twentieth century.

It can be said that his painting has not yet gained the attention of the critics already gained by his sculpture. Starting from the initial influences from Soffici, from the rediscovery of the strict structure of the Tuscan countryside landscape, Martini has been gradually making a sort of conversation and dialogue with most of the events of the twentieth century painting: from his early on in his career at the exhibition "Selvaggio" (The Wild), 1927, along with Soffici, Rosai , Lega, Morandi and Maccari, to the exhibition at the Cometa of 1939, where Soffici wrote about the young sculptor Martini: "I have seen the beginning and growth toward their perfect vitality of these gentle and sober images of naked youth, these strong figures made of terracotta or stone, these vigorous portraits - including the excellent one of the old author's mother. It is therefore a true joy to present what was in my eyes the young Martini, now adult brother in art, and to identify in him a working energy, genuine, fresh, and fruitful in the Italian sculpture of the new time." From then until the recent times, with tireless daily work around the paintings of these years, all the painting of Martini […] is a constant search, quasi-structural, run on certain themes: the hills of Seano, the woods, the still lifes, the big close-up of straw and twigs, the figures of the peasants, and the portrait.

Quinto Martini's working on specific subjects, his going again and again to the same compositions or landscapes with a nearly obsessive pursuit, his secluding himself in painting to rethink the terms of the development of the twentieth century art trends from the Futurism onward, is the line that has characterized the entire work of the artist. There is a passage in the testimony Martini made in 1964 on the occasion of the death of Soffici, which makes clear the secret obsession of his research as a painter, just in the words with which he describes his friend-Master: "You spoke of your torment of not being able to paint the countryside with which you were so familiar, with the simplicity and greatness you wanted, that you felt in you. And while we were talking about many different things, you were so intense that I had the feeling that you were still writing the most beautiful part of your Scoperte e massacri" [Discoveries and Massacres, a writing of Soffici].

And the torment "of not being able to paint the countryside with the simplicity … you wanted" which moved Soffici's way of painting according to Martini, is the same torment that moved the latter for decades. The stylistic phases of Martini's painting can be nowadays defined in their overall development: from the paintings of peasants of the thirties to the interiors with smoking people and the woods of the fifties; it is plain that to the initial strength of his figures, to the simplicity of a "primitive Tuscan" revised according to the artistic atmosphere of the twentieth century, the nag of a structuring concept overlaps, not lyrical and emotional any longer, but intellectual and rational. Relevant is, again, the testimony of Martini about Soffici: "I remember when you showed me for the first time photos of the paintings of Cézanne and you spoke to me of his painting". Soffici's words on Cézanne can be seen in the writing "Scoperte e massacri" (Discoveries and massacres) dated 1908: "Paul Cezanne represents a unifying desire of modern painting. ... In such moments, all was clear and consistent in his mind: no more clashes of different opinions, no more fragmentary misunderstandings; but a compact vision, genuine and free, ... Crazy and primitive, Cézanne was, but rather grumpy as the first Christian mystics: like Jacopone da Todi and Giotto."

But the "primitive" of Cézanne was for Soffici "the supreme expression of modernity", an expression difficult to take roots in a country like Italy, where "whatever can name the parrots writing on third pages of major newspapers, the masked brokers of illustrated magazines, and dusty professors paid to be gravediggers' in museums, does not know or understand, and therefore does not love, modernity". The "primitive" for Quinto Martini is no longer just "the supreme expression of modernity", which appeared to Soffici in the first decades of the century, in the wake of Cubism: "the primitive" becomes for him instead a rediscovery of essential significance, we would say "structuring", of nature and things. The presence of such a conception, a rediscovery of the Cézanne "crazy and primitive, … but rather grumpy … like Jacopone da Todi and Giotto", so far from the interpretations of Cézanne in a "classical" way needs however to be clarified: Martini did not want to bend to a dogmatic way of interpreting the themes of the twentieth century that somehow was "rhetoric and celebrative" but still equally distant from both civil and political rhetoric and lyricism o feelings. Painting the simplest things of the everyday life is not for him, as he himself says, like painting lilies and roses, the "luxurious lyric" that confuses scented fiction with the nature, but it is instead painting still lives where the bread, a glass, white beet cut with a hatchet and large gourds or meadows flowers thrown without scene on the table or even the bramble and straw, these are the simple things that animate his art work. And yet this is not "poetry" of the vernacular or the primitive, but instead the narrative of things of which daily existence is soaked. Efforts are made to paint potatoes and wood when it is known that they are the substance of things as like as any figurative hyperbole of "Chief World Systems".

This nag of Martini's search for a beauty that is inner in things without any emphasis, characterizes all his work and stands alongside rough sculptures like the man in the rain with a cardboard box on his head, and the smooth finesse of his young nude girls who caress themselves in love: these sculptures are seemingly different, almost strident among each other, but still animated by the same secret nag.

Critics has yet to assess this peculiarity that allowed Martini not to run aground on the shoals of the populism of the "Strapaese", and not even in the subsequent ones of the so-called "Mediterranean humanism".

The reasons for the search towards an almost primitive simplicity, characteristic of his early education with Soffici, perhaps had to compete soon with the other element that shaped the young Martini: the military service in Turin in 1928, the time of the first meeting, as he told me, with Carlo Levi and the cultural environment marked by the presence of Felice Casorati, and of the younger Francesco Menzio, Enrico Paulucci and Cesare Pavese. […]

Thus the presence of Levi became, after the mastering of Soffici, the second milestone of this "education in painting", but it will have greatly different meanings and outcomes; Soffici is the decisive model in the formation of the young Martini and leaves a definitive print throughout the course of his formal evolution. Soffici's models are soft, from the Florentine countryside so differently painted by Rosai, to the barefoot peasant women with long dresses and to the rough men whose faces are almost cut in stone, far from those of the underclass "omini" (little men ) of the other great Florentine artist of Toscanella street, will always torment the personal search of Martini because they were set in Quinto's universe at the time of his artistic birth: instead Levi, known in 1928 in Turin but not seen often until the forties and the World War II, will not give a clear print. Levi is not so much a stylistic point of reference but instead a fraternal presence, a fellow with whom to have a dialogue, and this dialogue must be somehow emerged as an encouragement to come out from the original world of Soffici. In the farewell pages dedicated to Soffici, written by Martini, it emerges the deep albeit controversial presence of Soffici: on the one hand Soffici appears as the first Master who shows confidence in the means of the young sculptor from Seano and also the intellectual that reveals Cézanne and Picasso to him, which places his artistic work in a space which is not the cramped and closed one of the academic tradition. On the other side, Martini feels the political limits of the personality of Soffici, his adherence to Fascism, so as it appears in the words of the old socialist mason Torquato Cecchi "like a child" who does not understand anything about politics. Hence the friendship with Levi comes as with an intellectual of opposite pole: a confirmation of a push to socialist ideals, to the peasants and workers world-class of Martini.

These are the years of the arrests, the long detention of the elder brother of Quinto in the fascist prisons, until the World War II and Quinto going underground, years that pushed in some way the artist to revise his artistic roots. Martini smiles at the critics who have tried to identify in his sculpture of the thirties and forties an affiliation to that sort of "Mediterranean humanism" between the two Wars, made of sun, sea and naked young men, which would have filled the artists of his generation: he tells me that he never tried that "lyrical purity", depicting the youthful beauty that someone has claimed as the sense of his sculpture at the time. Smiles at the thought of being associated in this search for Beauty to sculptors that he feels deeply foreign to his nature as Arturo Dazzi and Publio Morbiducci: "Misunderstandings intentionally created by those who want to see themselves rather than what I actually did: I've always put in the nudes something anticlassical. The rhetorical naked never was of my interest". After the War, in the fifties and sixties, Martini consciously start a review of its roots inspired by Soffici, and his paintings witness to this search: he reinterprets the fundamental episodes of the twentieth century and as in a laboratory revises again with fury the landscape of Seano, the still lifes, the woods and the peasants of his paintings in the light of the new language of Futurism and Cubism, until getting to the idea of a way of painting that abstracts those different languages experimentally.

It then opens up to intense lights, to the figures of men at field works, immersed in confetti of color, by which decorates the walls of his studio and those big temperas that he then rolled up one into another.

Sometimes the outcome appears hard, almost schematic: logs faceted wood and poplars on slopes voluntarily "cubist"; bottles, glasses and homemade bread, still lives imbued in gray misery; lumberjacks at the table with glasses and bottles of wine, that smoke clouds of "futurist program", a poor guitarist, homage to Picasso.

But suddenly the happy eye of this who is still a peasant boy lights itself up and then his hand turns to paint figures of women and children, illuminated by a shower of pink, yellow and blue, faces of mothers and children who face at the door or look at us behind the transparent glass of a window marked by rain.

Here, the usual grumpy Quinto appeases himself and smiles:

"I never had clear ideas of painting as I have now: I'm between light and shadow, the threshold that separates them is precise, yet subtle. Perhaps I could paint it but I still need to be a bit of time".

***

This essay, initially written on the occasion of the eightieth birthday of the artist and published shortly after his death in the journal Pietra Serena, n. 5/6, Summer-Autumn 1990, is republished in its original version the catalogue for the exhibition held in Florence in 1995: Quinto Martini. Sculture e dipinti – Opere 1925 – 1990, editied by Marco Fagioli, Galleria Il Ponte Publishing, Florence, 1995, pp. 13-17.

ITALIANO

ITALIANO ENGLISH

ENGLISH