QUINTO MARTINI - SCULPTURE by Marco Fagioli

Naked woman lying with hands in her hair

Naked woman lying with hands in her hairQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

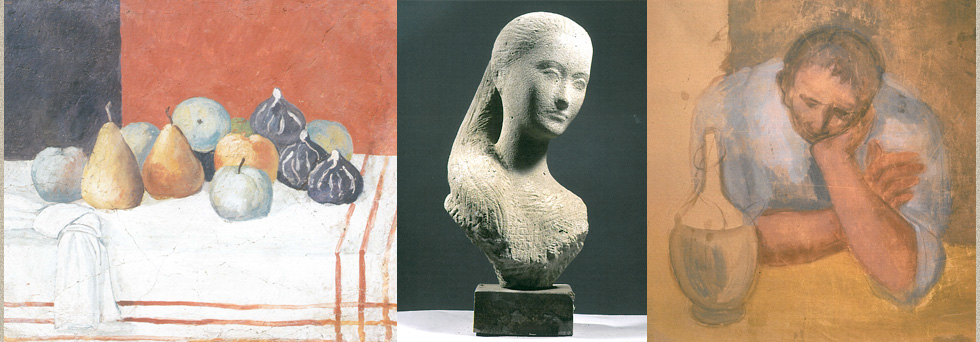

Portrait of Laura Soffici

Portrait of Laura SofficiQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

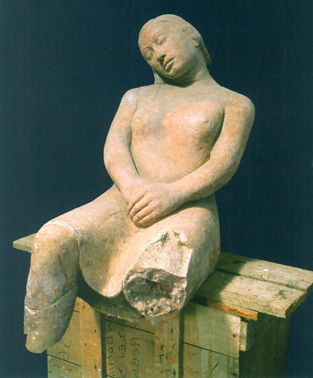

Woman sleeping, 1933

Woman sleeping, 1933Quinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

Portrait of woman, 1937

Portrait of woman, 1937Quinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

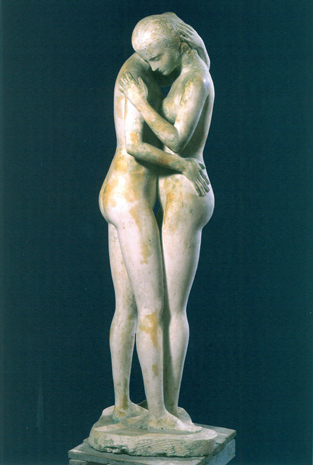

Friends

FriendsQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

Portrait of woman

Portrait of womanQuinto Martini Painter and Sculptor, AIÓN Publishing, 2004

Quinto Martini and the little bronzes

Quinto Martini intensely belonged to the culture of its origins, the land where he was born. The sights, the Seano valley, the hills of Carmignano and on their background the Montalbano, had a structuring meaning for the sculptor, almost inseparable from his work. Yet this sense of belonging has never had anything to do with the idea, widespread in the Tuscan culture of the twentieth century, of an almost ethnocentric pride, the narrow-minded provincial idea of being still the center of the world based on the dimension of its own centuries-old artistic tradition, from Giotto to Fattori, from Arnolfo di Cambio to Lorenzo Bartolini: a pride that had lethal effects on many artists peers and younger than Quinto.

His deep sense of belonging to this culture had not stopped Martini to look with interest elsewhere, to look at the world, despite the fact that his conditions of living were at times modest; and the art world was still, above all and having primacy, in the decades between 1920 and 1940, the one of the French Impressionism and Cubism that was the one that his Master, Soffici, mentioned as an example since the first visits that the young Quinto paid to his house in Poggio a Caiano.

Martini recounts in his diaries that it was in the library of Soffici that he saw for the first time reproductions of works by Paul Cézanne, Henri Rousseau, the Customs Officer, and a drawing by Picasso. This encounter with those artists and works took place when Soffici had already started, after 1920, his "call to order", the return to the figurative tradition of Italian art and the abandonment of the experimentalism of the historical Avant-garde that characterized the whole picture of the Master till his death. Modernity was intended by Soffici as a kind of adaptation of the great structural language of Cézanne to the Tuscan landscape. So the attention to the great European art was done with eyes yet turned to the Tuscan landscape, to its simple and plastic rules, to that codification established by centuries of tradition: the cubic farmhouse, the cypress, the rows of vines, the flint, and the freshly plowed fields. But the way to look at Cézanne was not the same of looking at Picasso which was developed later in the Cubist current, but back, almost like at the Cézanne seen, before the Cubist revolution, by the Tuscan painters who were in Paris at the beginning of the century, such as Alfredo Muller, Egisto Fabbri, Gustavo Sforni, and Eduardo Gordigiani.

This legacy of a codification inherited by Soffici, would have influenced the paintings of Quinto much more than his sculpture, that - stronger as art, and more difficult by nature, stony and not colored, plastic and not atmospheric, tactile and not visual as in the allegoric Blind of Gambassi - will take for Quinto Martini a completely independent tone from his Master's one.

It is in sculpture that Martini finds his more powerful vocation and develops a genuine vein, because in it the influence of Soffici was not relevant, or at least took place in a much more indirect way.

And it is in sculpture that Martini develops his artistic vein in a rigorous and absolute autonomy. It has been already said that Quinto choose since the very beginning, at the end of the '20s, his artistic referents in the great tradition of the Tuscan plastic fourteenth and early fifteenth century: its peremptory sentence was - "Soffici and the Nature were my only teachers" – but this sentence has to be read among the lines of a broader context.

In reality Martini well looked at other masters, who sometimes recalled in a direct way, others in a mediated way but always still explicit. Martini liked to present himself in a simple and categorical manner, concealing his profound knowledge of the sculpture, thus confirming the almost rude figure of the old craftsman, free from intellectualism and attitudes as fashion artist.

In 1990, when Quinto Martini reprinted in a volume at the Pananti Ed. three essays previously published in magazines about Donatello, Michelangelo and Rodin, with a foreword by Umberto Baldini, Martini wrote at the bottom of his preface: "To Mario, marble master from Prato, who in my distant adolescence inside the shed next to the walls of the Castle of the Emperor taught me with discipline how to use chisels and refine the tools of the art, with much gratitude, I dedicate these writings".

It is therefore to a "marble master," a craftsman and not another artist that Martini addressed his thanks, as if to claim the origin of his sculpture form anonymous "marble craftsmen", decorators of the Romanic parish and collegiate churches, men more incline to action than to abstract thinking.

This seemingly primitive soul, of popular and peasant origins, lived in the Quinto along with a deep desire to get a classical culture and therefore art and literature were for him the highways to get there. Martini conceived the art of little bronzes in a thorough sense, as one of the main genres of sculpture, and with the little bronzes he fully realized his ideal synthesis of the formal features of the great artistic tradition, which ranged from Donatello to Giambologna, and the forceful trends of modernity, from Degas to Maillol.

Martini has been a sculptor with a deep art culture and his bronze works are perhaps its most complete testimony. His biography shows us, after his training with Soffici, other the milestones: the collective exhibition at the "Selvaggio" (the Wild atelier) in February 1927; the decisive encounter with the sculptures of Aristide Maillol at the Venice Biennale of 1934, where Martini exhibited his great terracotta titled "Ragazza seanese" (The Seano Girl) and where the French master, then at the top of his fame, exhibited two sculptures, the nudes to the Monument to Cezanne (a plaster cast), and Venus (bronze), both "female nudes to be understood as typical in his work over the last decades". Then his friendship with Carlo Levi, most probably begun in Turin in 1928, during Quinto's military service, strengthened in the dark years of the World War II and when they were together in detention during the emergency of 1943, his participation in the group "Nuovo Umanesimo" (New Humanism) in 1947, which brought together painters like Ugo Capocchini, Emanuele Cavalli, Giovanni Colacicchi, Onofrio Martinelli, and the sculptor Oscar Gallo.

Other minor events sum in the early stages of Quinto Martini like his repeated participations at the Biennale, Triennial and Quadrennial, before and after the War; various exhibitions from the gallery of Milan Gian Ferrari, in 1941, after those of 1938 in Florence and Rome, at the gallery Cometa of Ms. Pecci Blunt, where he was introduced by Soffici; the exhibition of paintings on the "Mendicanti" (The Beggars), at the "Lyceum" gallery in Florence, which got censored by the fascists immediately after its opening in 1943.

Beyond Soffici, who presented the young artist from Seano in the "Frontespizio" magazine, important role in his artistic education was played by other decisive figures of the twentieth century Tuscan culture: Giovanni Papini, the post-futurist artisti who published the poems Pane e vivo and Soliloquio sulla poesia (1926) in the Vallecchi edition, that Quinto read immediately once published in 1927, in which the images of the countryside, the seasons and the agricultural world, shine with solemn tone, almost expressionist - "Gets on bare meadows the old spring / from rusty iron and steel skies". And further the Dino Campana's poems depicting chromatic landscapes of the "Canti orfici" (Orphic Songs), although Quinto, always anchored to the "style" of Soffici, did not share the "absence of classicism" and "the explosion of language" push "up to a total jam, as in Genoa" (Luigi Baldacci, 1985), of the great visionary from Marradi.

Finally, the playful and sometimes farcical vein of the poetry and prose by Aldo Palazzeschi, "the only true master of the clean avant-garde" (Luigi Baldacci, 1984), poet of the "color blue", to whom Martini made some memorable plastic portraits like the one with the hat and coat collar raised, taken in a cold winter day in Venice, a poet who seems to return with its most pictures to the colours of the Carnival.

However, despite these many different inspirations Martini always looked at Soffici as his main referent, and monitored his changes even when, as war approached, the project of "call to order" that the Master of Poggio a Caiano was having eventually succumbed to the new trends that came from outside; and the new trends were again coming from Picasso, that Picasso who the same Soffici had first discovered at the beginning of the century and from whom distanced himself later, pursuing the "call to order" idea that denied the prerequisites of the historical Avant-garde, of the Cubism, and finally of that Cézanne who, as acutely wrote Luigi Baldacci in 1979, "became a memory of the past, an inner possession, along with the knowledge that in his name the circle was actually closed (as Papini used to say) for the Western civilization, and that worth became, since then, to have fun painting the Tuscan countryside from the windows of Poggio a Caiano". And still the lesson of Soffici, contained in the book "Scoperte e massacri" (Discoveries and massacres) compiling pieces written from 1908 to 1915, that as Baldacci wrote was "a manifesto of the twentieth century", remained for Quinto his Polar Star.

In 1943, in the midst of catastrophe of war, the utopia of a "call to order" of Soffici proved impossible as it could not represent a world that no longer existed. Martini then turned vigorously to Picasso with his series of paintings "Mendicanti" (The Beggars), but looked to Picasso's blue period and not that of the dramatic Guernica, absolute synthesis of the three original avant-gardes of Cubism, Surrealism and Expressionism. It is not surprising that even Guttuso, who also kept a picture of Picasso's painting in his wallet, inspired his Crucifixion of Bergamo to the most figurative and less violent Cubism.

Quinto will be therefore inspired, for his bas-relief "Il riposo del mendicante" (The beggar's rest) dated 1946, by The old blind guitarist of Picasso dated 1903, made at the Art Institute of Chicago, thus a work of almost half a century before.

Some memories of the Guernica, 1937, will be only visible in the terracotta "Sotto il bombardamento" (Under the bombing), 1944-45.

During the following decades, from 1950 to 1980, Quinto consistently followed his personal trend in sculpture, becoming - as I expressed in my intervention at the conference organized for the centenary of his birth in Seano in October 2008 - "A modern anti-modern".

A modern in the sense of belonging to that current of the twentieth century that has faced a great dilemma: the fact that in the end moderns are also anti-moderns, for their continuous experiencing without nevertheless leaving the groove, or better the paths, even different ones, of tradition.

It becomes then clear that in the twenty years, running from 1945 to 1965, in which Martini was often engaged in themes of social interest, as evidenced by his land laborers subjects, his hosts inspired to Arnolfo, his skinners and his peasant chasing ducks, alongside the increasing number of female nudes and portraits, has never felt to the more anecdotal layers of the Italian Neorealism. The subjects, the themes have been for him increasing opportunities to continue shaping his world of images of the Nature.

Lucia Minunno excellently drew [in the monograph dedicated to the little bronzes, see below] the journey of Quinto Martini sculpture, where the little bronzes have a fundamental role as a laboratory for the greatest works and also as autonomous themes.

From: Marco Fagioli, Quinto Martini between modernity and tradition, in Quinto Martini. The little bronzes, edited by Lucia Minunno, AIÓN Editions, Florence, 2010, pp. 9-13.

ITALIANO

ITALIANO ENGLISH

ENGLISH