"I grasp hold of art and she will not let me go and I do not give her up"

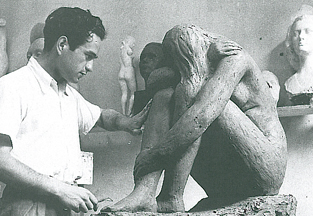

The dominant theme of the life of Quinto Martini, constant in self-presentations he made, was his passion for art and for his artistic work. Working for him was a "disease" and equally a "therapy", an inexhaustible reason of pleasure and in any case always a compelling reason with his life.

Quinto Martini considered art an absolute and almost incommunicable dimension of the spirit "of art an artist speaks seriously only when he makes it" writes in a note without date, and an artist reveals himself only through his works: "I work a lot, because I believe that only working it is possible to solve all those deep problems of art that intelligence could never settle through abstraction. An artist who has a commitment to himself has a commitment with the society". Visit Biography page »

The dominant theme of the life of Quinto Martini, constant in self-presentations he made, was his passion for art and for his artistic work. Working for him was a "disease" and equally a "therapy", an inexhaustible reason of pleasure and in any case always a compelling reason with his life.

Quinto Martini considered art an absolute and almost incommunicable dimension of the spirit "of art an artist speaks seriously only when he makes it" writes in a note without date, and an artist reveals himself only through his works: "I work a lot, because I believe that only working it is possible to solve all those deep problems of art that intelligence could never settle through abstraction. An artist who has a commitment to himself has a commitment with the society". Visit Biography page »

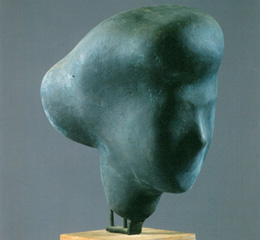

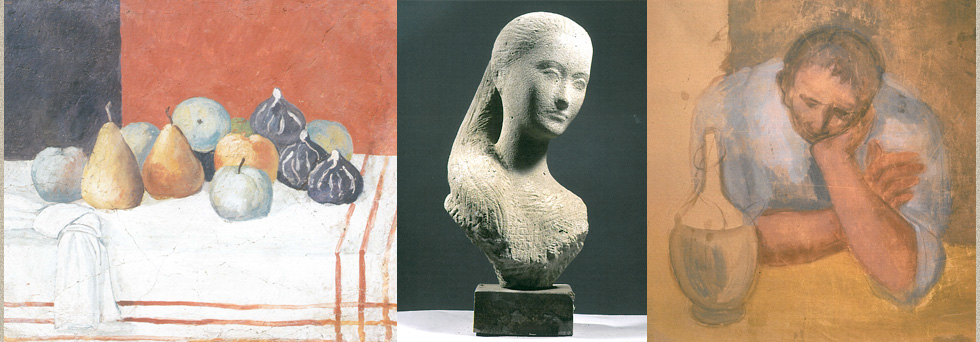

In sculpture Martini develops his artistic vein in a rigorous and absolute autonomy. It has been already said that Quinto choose since the very beginning, at the end of the '20s, his artistic referents in the great tradition of the Tuscan plastic fourteenth and early fifteenth century: its peremptory sentence was - "Soffici and the Nature were my only teachers" – but this sentence has to be read among the lines of a broader context.

In reality Martini well looked at other masters, who sometimes recalled in a direct way, others in a mediated way but always still explicit. Martini liked to present himself in a simple and categorical manner, concealing his profound knowledge of the sculpture, thus confirming the almost rude figure of the old craftsman, free from intellectualism and attitudes as fashion artist.

In 1990, when Quinto Martini reprinted in a volume at the Pananti Ed. three essays previously published in magazines about Donatello, Michelangelo and Rodin, with a foreword by Umberto Baldini, Martini wrote at the bottom of his preface: "To Mario, marble master from Prato, who in my distant adolescence inside the shed next to the walls of the Castle of the Emperor taught me with discipline how to use chisels and refine the tools of the art, with much gratitude, I dedicate these writings".

It is therefore to a "marble master," a craftsman and not another artist that Martini addressed his thanks, as if to claim the origin of his sculpture form anonymous "marble craftsmen", decorators of the Romanic parish and collegiate churches, men more incline to action than to abstract thinking. Visit Sculpture page »

In 1990, when Quinto Martini reprinted in a volume at the Pananti Ed. three essays previously published in magazines about Donatello, Michelangelo and Rodin, with a foreword by Umberto Baldini, Martini wrote at the bottom of his preface: "To Mario, marble master from Prato, who in my distant adolescence inside the shed next to the walls of the Castle of the Emperor taught me with discipline how to use chisels and refine the tools of the art, with much gratitude, I dedicate these writings".

It is therefore to a "marble master," a craftsman and not another artist that Martini addressed his thanks, as if to claim the origin of his sculpture form anonymous "marble craftsmen", decorators of the Romanic parish and collegiate churches, men more incline to action than to abstract thinking. Visit Sculpture page »

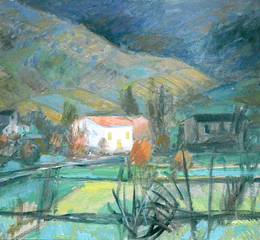

In the clear light of his studio in Seano and in the more watery light of his studio in dei Della Robbia street in Florence, Quinto Martini has been weaving for decades, through painting, a kind of ongoing dialogue with himself, the men, and the culture of the twentieth century.

It can be said that his painting has not yet gained the attention of the critics already gained by his sculpture. Starting from the initial influences from Soffici, from the rediscovery of the strict structure of the Tuscan countryside landscape, Martini has been gradually making a sort of conversation and dialogue with most of the events of the twentieth century painting: from his early on in his career at the exhibition "Selvaggio" (The Wild), 1927, along with Soffici, Rosai , Lega, Morandi and Maccari, to the exhibition at the Cometa of 1939, where Soffici wrote about the young sculptor Martini: "I have seen the beginning and growth toward their perfect vitality of these gentle and sober images of naked youth, these strong figures made of terracotta or stone, these vigorous portraits - including the excellent one of the old author's mother. It is therefore a true joy to present what was in my eyes the young Martini, now adult brother in art, and to identify in him a working energy, genuine, fresh, and fruitful in the Italian sculpture of the new time." From then until the recent times, with tireless daily work around the paintings of these years, all the painting of Martini […] is a constant search, quasi-structural, run on certain themes: the hills of Seano, the woods, the still lifes, the big close-up of straw and twigs, the figures of the peasants, and the portrait. Visit Painting page »

It can be said that his painting has not yet gained the attention of the critics already gained by his sculpture. Starting from the initial influences from Soffici, from the rediscovery of the strict structure of the Tuscan countryside landscape, Martini has been gradually making a sort of conversation and dialogue with most of the events of the twentieth century painting: from his early on in his career at the exhibition "Selvaggio" (The Wild), 1927, along with Soffici, Rosai , Lega, Morandi and Maccari, to the exhibition at the Cometa of 1939, where Soffici wrote about the young sculptor Martini: "I have seen the beginning and growth toward their perfect vitality of these gentle and sober images of naked youth, these strong figures made of terracotta or stone, these vigorous portraits - including the excellent one of the old author's mother. It is therefore a true joy to present what was in my eyes the young Martini, now adult brother in art, and to identify in him a working energy, genuine, fresh, and fruitful in the Italian sculpture of the new time." From then until the recent times, with tireless daily work around the paintings of these years, all the painting of Martini […] is a constant search, quasi-structural, run on certain themes: the hills of Seano, the woods, the still lifes, the big close-up of straw and twigs, the figures of the peasants, and the portrait. Visit Painting page »

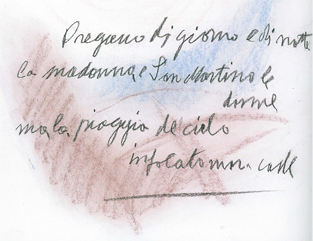

The fundamental feeling that animates his literary work is the emphasis of the strongest authenticity and true degree of human civilization of the countryside.

This leads Quinto to represent, in subdued and non-rhetorical terms, the pride of the peasant, his instinctive ability to react to situations in a more harsh social reality characterized by shortages and strong class differences and finally the formation, within the peasant's soul, of a hope and a political will aimed at "creating a world where there is no people dying of hunger and none who instead dies from too much eating" which expressed the adherence of many to communism against fascism.

The universe of values witnessed in "I giorni sono lunghi" is also present in the pages of "Chi ha paura va alla guerra", where the comparison between a conscious secular option that relies on the will of man and wants to be an effective and popular mercy regarded by the author alive, authentic and worthy of the highest respect, but basically ineffective, provides an ethical and civil (and even religious) character to the theme addressed. Visit Writings page »

This leads Quinto to represent, in subdued and non-rhetorical terms, the pride of the peasant, his instinctive ability to react to situations in a more harsh social reality characterized by shortages and strong class differences and finally the formation, within the peasant's soul, of a hope and a political will aimed at "creating a world where there is no people dying of hunger and none who instead dies from too much eating" which expressed the adherence of many to communism against fascism.

The universe of values witnessed in "I giorni sono lunghi" is also present in the pages of "Chi ha paura va alla guerra", where the comparison between a conscious secular option that relies on the will of man and wants to be an effective and popular mercy regarded by the author alive, authentic and worthy of the highest respect, but basically ineffective, provides an ethical and civil (and even religious) character to the theme addressed. Visit Writings page »

VIDEO

Directed by Federico Bondi

Production of Teresa Bigazzi and Luciano Martini

Music by Éric Satie

Trailer of documentary "Quinto Martini"

Release date 1999

Duration 34' minutes.

Release date 1999

Duration 34' minutes.

ITALIANO

ITALIANO ENGLISH

ENGLISH